The escalating demand for livestock products in developing and developed countries coupled with steadily increasing temperatures is an unbearable situation, with costly infrastructural investments needed to overcome challenges of thermal environments and also to increase their productivity has become a serious concern all over the world. Annual losses of cattle products due to heat stress is about US$1·26 billion for dairy and beef cattle herds in the USA in the early 2000s. It has being projected that income losses of £40 million in the UK dairy herd might be experienced from year 2080 and above if proper measures are not taken talkless of other livestock.

Stress is a reflex reaction of animals in harsh environments and causes unfavorable consequences ranges from discomfort to death.

Heat stress in livestock occurs when the environment is too hot and humid, making it difficult for animals to cool down. It is one of the major impact of climate change on livestock raised in both intensive and extensive production systems.

When environmental conditions challenge the animal’s thermoregulatory mechanisms, heat stress arises. This means that animals become affected when there is an imbalance between metabolic heat production inside the animal body and its dissipation to the surroundings, results to heat stress (HS) under high air temperature and humid climates. It result from combinations of temperature, humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed beyond the ability of an animal to thermoregulate.

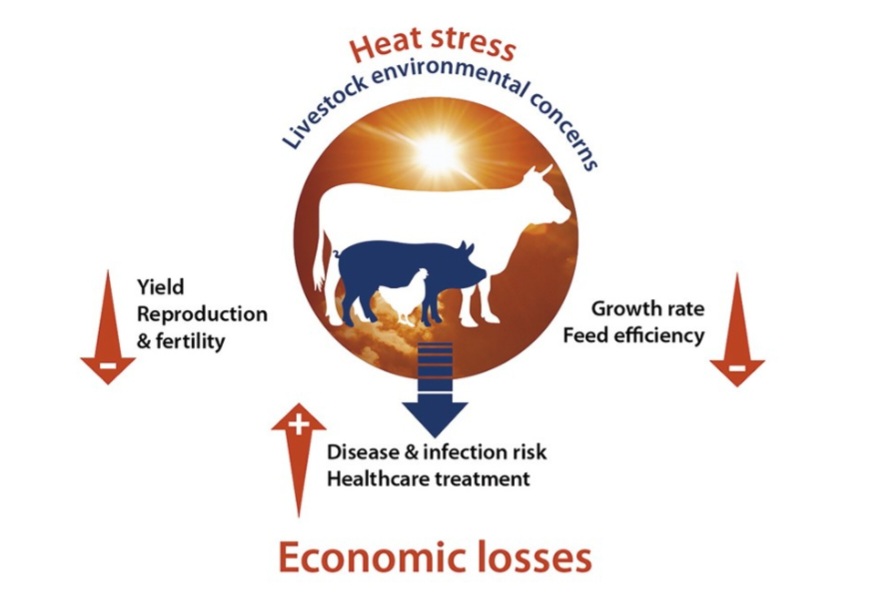

The effects of heat stress include reduced productivity, reduced animal welfare, reduced fertility, increased susceptibility to disease, and in extreme cases increased mortality, and affect all domesticated species.

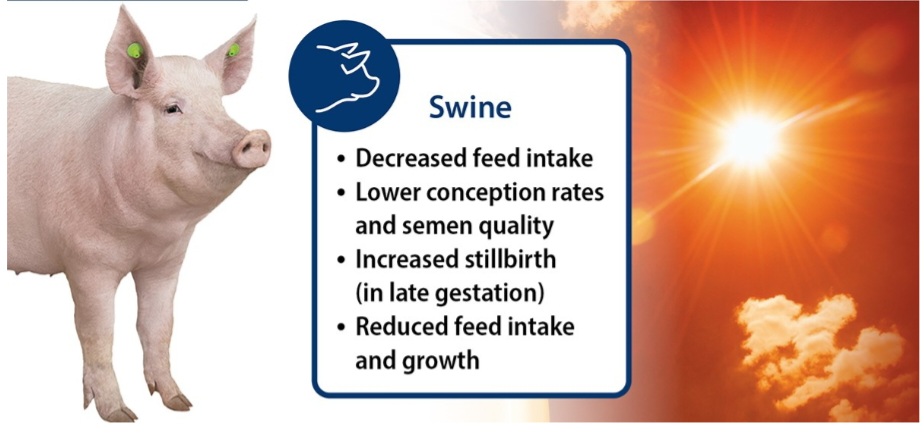

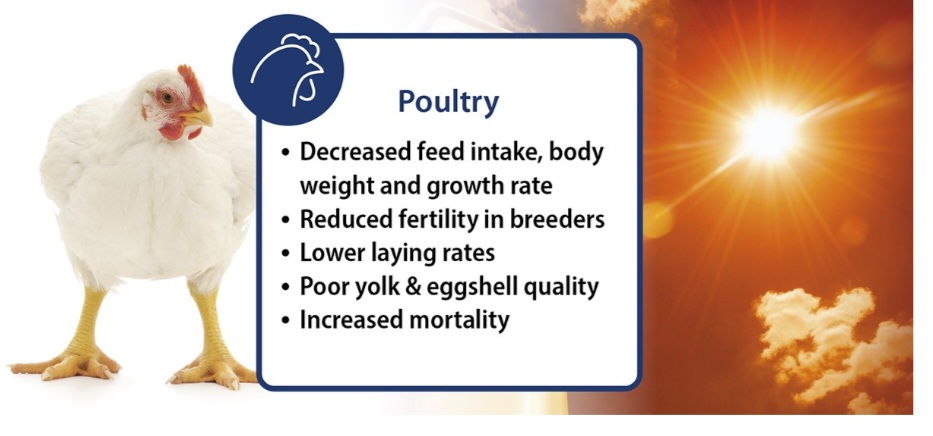

At temperatures higher than an animal’s thermoneutral zone, heat stress can affect liveweight gain, milk yield, and fertility. For example, in cattle rearing, depending on species and breed, can experience thermal stress at temperatures higher than 20°C. Temperature increases of 1.5°C and above may exceed limits for normal thermoregulation of poultry (broiler and layer chickens), and pigs, and could result in persistent heat stress for these animals in a range of different environments. In Brazil, high ambient temperatures (29–35°C) reduced average daily weight gain in growing‐finishing pigs by nearly 10% and feed intake by nearly 14% compared with a thermoneutral environment (18–25°C).

Indigenous or local poultry are often assumed to be hardy and well adapted to stressful environments Compared to exotic breeds.

In the case of sheep and goats, the direct effects of higher temperatures on them may be less severe, though goats are better able to cope with multiple stressors than sheep.

At higher temperatures, animals reduce their feed intake by 3–5% per additional degree of temperature, reducing productivity.

Animal welfare may also be negatively affected by heat stress even in the absence of effects on productivity, at least in the short term. It can increase respiration and mortality, reduces fertility, modifies animal behaviour, and suppresses the immune and endocrine system, thereby increasing animal susceptibility to some diseases.

The ways a particular animal will respond to heat stress, and when it will result to production losses vary widely. This variation depend on factors such as species, breed, age, genetic potential, physiological status, nutritional status, animal size, and previous exposure, with high‐yielding individuals and breeds the most susceptible. For example, dairy cows are generally more susceptible than beef cattle, and temperate Bos taurus breeds tend to be more susceptible than tropically adapted Bos indicus cattle and their crosses . Within the dairy breeds, Holsteins are less heat tolerant than other breeds such as Jersey and Brown Swiss, in that they have a higher core temperature, are larger and thus have a lower skin surface to mass ratio, have thicker coats, and higher yield potential etc. Therefore, the effect of heat stress can result to changes that affect the economic performance of dairy and beef production systems.

CAUSES OR FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO HEAT STRESS IN ANIMALS

Heat stress in livestock do occur when environmental conditions make it difficult for animals to regulate their body temperature. This can happen when temperatures, humidity, solar radiation, and wind speed are too high.

Climate change can also be a major cause of heat stress in livestock.

a. RISING TEMPERATURES: Climate change is causing global temperatures to rise, which increases the frequency and intensity of heat waves. When the temperature is higher than the animal’s normal body temperature, heat stress will occur

b. MORE EXTREME HEAT WAVES: Heat waves are becoming more frequent and longer lasting.

c. DENSE STOCKING DENSITY: Overcrowding in barns can hinder heat dissipation. Thus, affect animals welbeing.

d. LACK OF SHADE AND VENTILATION: Inadequate access to shade and poor ventilation in barns exacerbates heat stress.

e. HIGH HUMIDITY: High relative humidity limits the ability of animals to cool down through evaporative cooling.

c. SLOW AIR MOVEMENT: When there is not enough air movement to cool the animal. The animals become heat stressed.

d. SOLAR RADIATION: When the animal is exposed to the sun, body temperature may rise.

ANIMALS AT RISK OF HEAT STRESS

Animals at high risk of heat stress include:

a. young animals

b. dark coloured animals

c. animals that have been sick or have a previous history of respiratory disease

Heat stress tolerances can also vary between and within a species, for example:

i. pigs become heat stressed at a lower temperature level and are very prone to sunburn.

ii. sheep that are newly shorn are at risk of heat stress and sunburn due to lack of insulation from heat provided by wool

iii. high producing dairy cows are more affected by extreme heat than lower producing cows

iv. lactating cattle are more susceptible than dry cows because of the additional metabolic heat generated during lactation

v. beef cattle with black hair suffer more from direct solar radiation than those with lighter hair, although those with pink skin are at risk of sunburn

vi. Holsteins are less tolerant than Jersey cows

British breeds of sheep and cattle are less tolerant than merino or tropical beef breeds

heavy cattle over 450kg are more susceptible than lighter ones.

Cattle, alpacas and llamas are more prone to heat stress than sheep and goats

These types of animals should be watched more closely for signs of heat stress during days of high temperature.

EFFECTS OF HEAT STRESS ON LIVESTOCK

The foremost reaction of animals under thermal weather is increase in respiration rate (RR), rectal temperature (RT) and heart rate (HR). It directly affect feed intake thereby reduces growth rate, milk yield, reproductive performance, and even death in extreme cases. Dairy breeds are typically more sensitive to HS than meat breeds, and higher producing animals are susceptible since they generates more metabolic heat. HS suppresses the immune and endocrine system thereby enhances susceptibility of an animal to various diseases. Hence, sustainable dairy farming remains a vast challenge in these changing climatic conditions globally.

Some of the effects of heat stress on livestock include;

-Reduced milk production

-Reduced fertility

-Increased disease susceptibility

-Increased mortality

-Reduced dry matter intake

-Increased lameness

-Shorter gestation periods

-Calves with lower birth weights

a. REDUCED PRODUCTIVITY: Heat stress can reduce liveweight gain, milk yield, and fertility.

b. COMPROMISED ANIMAL WELFARE: Heat stress can negatively affect animal welfare, even if it doesn’t affect productivity.

c. METABOLIC ALTERATIONS: Heat stress can cause metabolic alterations, oxidative stress, and immune suppression.

d. REDUCED MILK PRODUCTIVITY: Animals may reduce their feed intake, which can lead to lower milk yield and meat production. In the case of dairy animals, there is usually a significant decline in milk production as the animal prioritizes cooling mechanisms over milk synthesis.

e. REDUCED FERTILITY: Heat stress can affect fertility in both male and female animals. It can disrupt estrous cycles, leading to reduced fertility and increased days open in dairy cows.

f. INCREASED SUSCEPTIBILITY TO DISEASE: Heat stress can suppress the immune system, making animals more likely to get sick

g. INCREASED MORTALITY: In extreme cases, heat stress can lead to death

h. DECREASED FEED INTAKE:

Under heat stress, dairy animals consume less feed, impacting their overall energy intake and further reducing milk yield.

i. ALTERED MILK COMPOSITION:

Heat stress can change the composition of milk, affecting the levels of fat, protein, and lactose.

j. PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES:

Increased body temperature, rapid respiration rate, and changes in blood parameters are common physiological responses to heat stress.

k. BEHAVIORAL CHANGES:

Dairy animals under heat stress may exhibit altered behavior like reduced lying time, increased panting, and less activity.

SIGNS OF HEAT STRESS IN LIVESTOCK

There are many signs of heat stress that livestock farmers should look for in their animals. Some general signs include:

-Panting

-Increased respiration rate

-Increased water intake

-Loss of appetite

-Listlessness or lethargy

-Increased salivation

-In severe cases, may become unconscious, Collapse or seizure may occur

-Excessive panting

-Drooling

-Bright red gums

-Vomiting or diarrhea

-Weakness, dazed expression, or incoherent behavior

1. PANTING: Panting is a physiological response and a sign of heat stress which animals and humans use to cool down by rapidly breathing. It increases the evaporation of moisture from the mouth and respiratory tract, thereby releasing heat from the body. When the environment is hot, increased panting is triggered to compensate for the rising internal temperature.

2. INCREASED RESPIRATION RATE: An increased respiration rate is a sign of heat stress. Heat stress activate the body’s thermoregulatory system, triggering increased breathing to facilitate heat loss through evaporation from the lungs. When the body is overheated, it attempts to cool itself down by panting, which increases the rate of breathing, allowing for more evaporation of moisture from the lungs and thus releasing heat from the body; essentially, faster breathing helps to dissipate excess heat.

3. INCREASED WATER INTAKE: Heat stress can have a significant effect on production and reproduction so it is important that shelter and a plentiful amount of cool water are supplied.

In times of excessive heat, livestock may crowd around water sources and place greater demand on water supplies. Birds like fowls in battery cages can be supplied cold water to cool their body system.

HEAT can also affect feeding and drinking troughs and other farm equipments. During cool months, routine farm maintenance should be done to check all troughs and water lines, so as to ensure they do not break down in the hotter months. For example, service pumps and replace seals if necessary. Check floats on troughs.

Water lines should be buried at least 15cm (6 inches) deep to prevent them heating up the water prior to entering the water point

It is important to note that shelter and water should be close together, care should be taken with livestock so that this does not result in animals camping around the water source, causing overcrowding and preventing all animals from accessing water. Ensure enough shelter and trough are provided so that all stock have access to water. Placement of troughs should also be carefully considered to prevent animals crowding between fences and the trough.

4. LOSS OF APPETITE: Heat stress causes loss of appetite primarily because the body prioritizes cooling itself down over digestion, meaning that eating generates additional heat which the body tries to avoid when already overheated. This is a thermoregulation mechanism where the body naturally reduces food intake in hot environments to prevent further heat production through digestion. Also, the production of hunger hormones are affected. Thus, leading to potential decreased in feeling of hunger.

5. DEHYDRATION: Excessive sweating during heat stress can lead to dehydration, which can also contribute to a loss of appetite.

6. LISTLESS OR LETHARGY: When temperature is high, the body has to work hard to keep cool. The body becomes dehydration and coupled with poor sleep result in feeling of tiredness. Fatigue is also a sign of tiredness. Thus need for the animal to rehydrate and rest.

7. INCREASED SALIVATION: Heat stress causes increased salivation in livestock. Salivation is a physiological response used primarily as a cooling mechanism, where the animal produces more saliva to facilitate open-mouth breathing (panting), which helps evaporate moisture from the tongue and oral cavity, thus lowering their body temperature. Essentially, the increased saliva acts as a cooling agent when evaporated through panting.

8. IN SEVERE CASES MAY BECOME UNCONSCIOUS: Heat stress in livestock can lead to dizziness, nausea and weakness. It also result in brain dysfunction with less blood flow to the brain. Thus resulting in lose of conciousness.

SIGNS OF HEAT STRESS IN SPECIFIC TYPES OF ANIMALS

1. HORSES:

Horses should not be exercised during hot weather but rather early morning and late afternoon/evening when it is coolest. Horses that are heat stressed may show signs of excessive sweating and reduced feed intake. Therefore, electrolytes can be added to their feed to replace essential salts lost through sweating.

Heat stressed horses can be cooled down by hosing with cool water, starting from the feet and moving up slowly, sponging with water or by placing wet towels over them.

Excess water must be scraped off afterwards unless there is a good breeze, as water in the coat on a hot, humid, still day will act as an insulator and it will quickly warm up again.

2. CATTLE:

Cattle that are heat stressed will show increased respiration rates as they try to cool themselves down. If cows are taking more than 60 breaths per minute, then, there is need to take action.

Cattles need to be provided plenty of shade as this can reduce the amount of solar radiation received by the cow by up to 50%.

Paddock rotation can be altered so that the cattle are in paddocks that are close to the dairy to reduce the distance they have to walk in extreme heat.

Sprinklers and shade can also be used in holding yards. To be effective, the sprinklers must wet the cows to the skin. Air flow is also important. Sprinklers have been found to improve milk production, reduce fly irritation and make for more contented cows in the shed with better milk let down.

Cattle should be allowed to drink plenty of water on the way to and from the dairy pen. Cows can also cool themselves by standing in cold water which allows them to disperse some of their heat load so access to a dam or other source of cool water can be useful in reducing heat stress.

3. PIG:

Pig in pen are usually provided drinking water out of a large bucket.

Pigs are highly susceptible to heat stress and sunburn, and should not be exposed to long periods of direct sunlight or extremes of temperature. Providing outdoor pigs with sufficient water and mud hole areas is extremely important when temperatures are above 25°C.

Pigs cannot effectively sweat because they have very few functional sweat glands relative to their body size, meaning sweating is not a primary way for them to cool down. Instead, they rely on activities like wallowing in mud or water to regulate their body temperature.

They also try to cool themselves by:

-increasing water intake

-lying on a cool surface

-panting

-reducing feed intake

-Transporting pigs in the heat is not adviceable, it is best to avoid transporting pigs in hot or humid conditions.

If transport is unavoidable, pigs should be transported in a covered and well ventilated trailer to avoid sunburn. Loading density should be reduced by at least 10% if the ambient temperature rises above 25°C to allow all pigs to be able to lie down. Pigs should be unloaded immediately on arrival at destination unless facilities exist for vehicles to park in a roofed area with spray facilities.

All procedures involving pigs including holding and selling should be conducted under a roofed area.

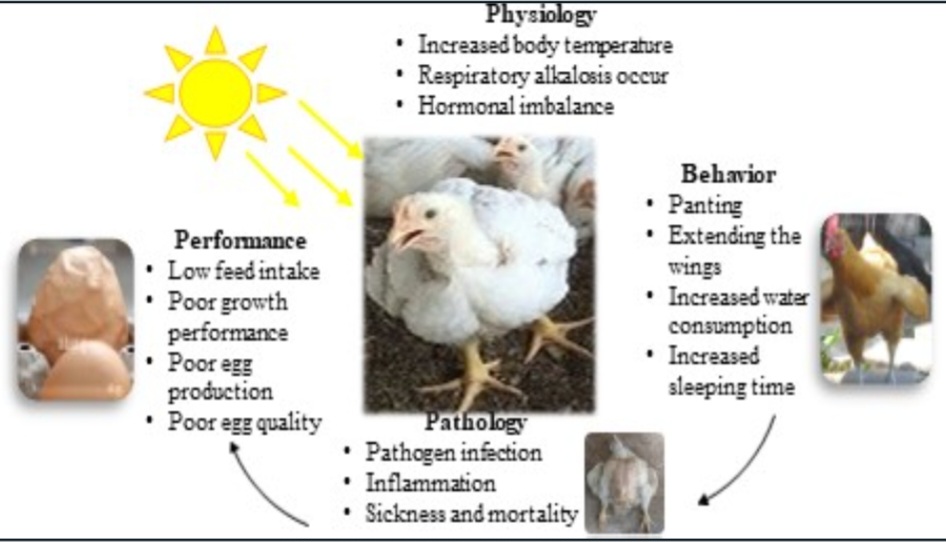

4. FOWLS:

In intensively housed fowl, high temperatures causes distress. To manage this distress, farmers uses foggers, roof sprinklers, fans, cold drinks, electrolyte drugs, glucose etc or other systems to control heat buildup within the poultry housing. Foggers are less effective if humidity reaches above 80% and temperature rises above 30°C. In these conditions mechanical ventilation must be provided for the fowls.

Birds can also be protected from overheating by providing enough space and not overcrowding the birds. This will facilitate heat loss, and temperature control systems must be in place to prevent ambient temperatures at bird level exceeding 33°C.

The construction and positioning of nest boxes should be such that they avoid becoming heat traps.

5. DOGS:

There are different types of dogs used for different purposes. Some are pets, some for security, some for farm work etc.

Cattle dog are used to watch over cattles on farm. They

stand in sunshine watching over the grazing cattle. This work dogs should only be allowed to carry out their duties during the cool times of the day, and they must have regular breaks with access to water and shade. Herders should carry water with them at all times and offer small amounts to their work dogs often.

If a dog is suffering from heat stress immediately stop it’s work, find the nearest water trough and put it in, or wet it down with a hose. Offer it cool water and place it in the shade and a breeze if possible. Seek veterinary assistance if it does not respond quickly.

Ensure the working dogs have access to shade and a source of clear fresh water at all times when they are kennelled or resting.

Metal kennels should be placed under the shade. Ice cubes can be put in the dog’s water bowl to keep it cool.

Dogs should not be left tied up on the back of a ute in the sun. On days over 28°C, dogs must have a layer of insulating material between them and the metal tray. Dogs have the following signs of heat stress:

-dry nose (caused by dehydration)

-weakness

-muscle tremors

-collapse

-Cats, dogs and other pets

Always provide plenty of cool, clean water and shade for the animal. When away from home, carry a thermos filled with fresh, cool water. Pet dogs should be left at home as much as possible. They will be much more comfortable in a cool home than riding in a hot car. If a pet must be taken along for the ride, they should not be left alone in a parked vehicle. Even with the windows open, a parked car can quickly become a furnace. On days with temperature over 28°C, dog must not be left, or any other animal, in a vehicle unattended to for more than 10 minutes.

Do not force animal to exercise in hot, humid weather. Exercise pets in the cool of the early morning or evening. In extremely hot weather, do not leave dogs standing on the street, and keep walks to a minimum. Because a dog is much closer to the hot asphalt, its body can heat up quickly, and its paws can sustain burns or injuries.

Animals can get sunburned too. Protect hairless and light-coated dogs and white cats with sunscreen when the animal will be outside in the sun for an extended period of time. Put sunscreen or zinc on exposed areas of pink skin. Animals with long coats can be clipped to increase comfort in hot weather.

Smaller animals

Small animals such as rabbits and guinea pigs can become heat stressed when temperatures increase over 21°C so it is important that their enclosures are in the shade and that they have plenty of clean cool water.

Remember, the most important things that can be done to animals in hot weather is to provide them with rest and shade in the hottest parts of the day, and plenty of clean cool water

CLIMATE CHANGE AND HEAT STRESS

Sustainability in livestock production system is largely affected by climate change.

Climate change is one of the major threats for survival of various species, ecosystems and the sustainability of livestock production systems across the world, especially in tropical and temperate countries. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported that temperature of the earth has been increased by 0.2°C per decade and also predicted that the global average surface temperature would be increased to 1.4-5.8°C by 2100. It was also indicated that mainly developing countries tend to be more vulnerable to extreme climatic events as they largely depend on climate sensitive sectors like agriculture and forestry. Recently, Silanikove and Koluman also forecasted the severity of heat stress (HS) issue as an increasing problem in near future because of global warming progression.

The thermoneutral zone (TNZ)[ the range of temperatures at which the body can maintain its core temperature without changing its metabolic rate] of dairy animals ranges from 16°C to 25°C, within which they maintained a physiological body temperature of 38.4-39.1°C. However, air temperatures above 20-25°C in temperate climate and 25-37°C in a tropical climate like in India and Africa enhance heat gain beyond that lost from the body and induces HS. As a results, body surface temperature, respiration rate (RR), heart rate and rectal temperature (RT) increases which in turn affects feed intake, production and reproductive efficiency of animals.

Homeotherms animals ( animals that maintain a stable internal body temperature, regardless of the temperature around them) can resist HS up to some extents depending on species, breed and productivity. Among dairy animals, goats are the most adapted species to imposed HS in terms of production, reproduction and also to disease resistance. Studies had stipulated that native breeds survive and perform better to heat stress as compared to exotic breeds and their crosses under tropical environmental conditions.

Due to the fact that the native breeds have evolved over generations to adapt to the local climate, they have developed traits like lighter hair coats, efficient sweating mechanisms, and smaller body sizes that help them dissipate heat more effectively in hot environments. Exotic breeds in comparison lack these adaptations and struggle to cope with extreme temperatures.

TRAITS THAT MAKE NATIVE BREEDS TO BE MORE HEAT TOLERANT COMPARED TO EXOTIC BREEDS

a. GENETIC ADAPTATION : From researches and breeding, native breeds have being descovered to develop genetic traits that enable them to thrive in hot climates. Such traits include; higher sweat gland density, better blood circulation to the skin, and a lower metabolic rate which generates less heat. While exotic breeds, due to their genetic makeup developed in cooler climates, often struggle to regulate body temperature in hot environments, leading to reduced productivity and potential health issues.

b. COAT COLOUR AND HAIR TYPE: Many native breeds have lighter coloured coats or sparse hair, which helps reflect sunlight and reduce heat absorption compared to the thicker, darker coats of exotic breeds.

c. BODY SIZE: Native breeds possess smaller body size which allows for better heat dissipation as they have a larger surface area relative to their volume. While Larger body size and heavier muscle mass exotic breeds can generate more metabolic heat, making it harder to cool down.

d. BEHAVIORAL ADAPTATIONS:

Native animals may also exhibit behavioral adaptations to heat stress, such as seeking shade during the hottest part of the day or altering grazing patterns to cooler times etc.

IMPACT OF HEAT STRESS (HS) ON LIVESTOCK PERFORMANCE, PRODUCTIVITY AND HEALTH

EFFECTS OF HS ON HEALTH OF DAIRY ANIMALS

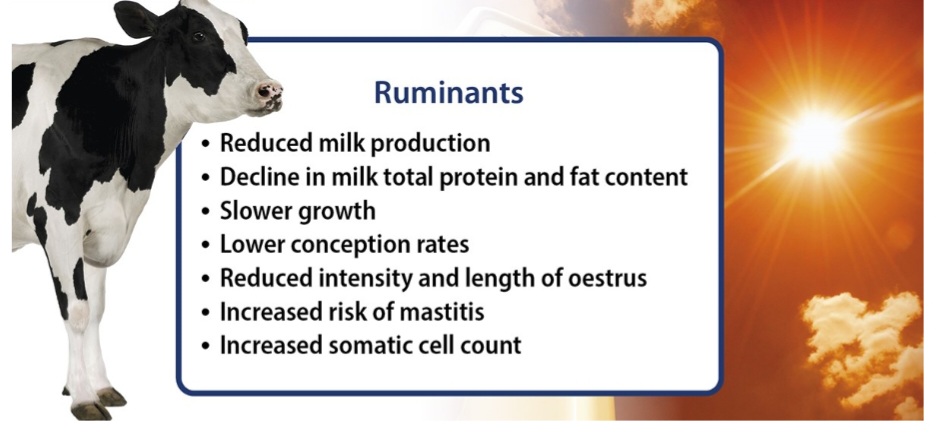

HS affects health of dairy animals by imposing direct or indirect effects in normal physiology, metabolism, hormonal, and immunity system. It significantly impact dairy animals by causing a decrease in milk production, reduced feed intake especially dry matter intake, alter milk composition, impaired reproductive performance, potential health complications, and pregnancy rates. Heat stress also leads to increased lameness, disease incidence, days open and death rates. All these are primarily due to the inability to effectively dissipate excess body heat in high temperature environments and can lead to significant economic losses for dairy farmers.

EFFECT OF HEAT STRESS ON FEED INTAKE AND RUMEN PHYSIOLOGY OF LIVESTOCK

Increase in environmental temperature has a direct negative effect on appetite center of the hypothalamus, therefore decrease feed intake. Feed intake begins to decline at air temperatures of 25-26°C in lactating cows and reduces more rapidly above 30°C in temperate climatic condition and at 40°C it may decline by as much as 40%. While in dairy goats, a decrease of about 22-35% may occur and 8-10% in buffalo heifers. Reducing feed intake is a way to decrease heat production in warm environments. Feeding is one of the ways that increases heat in livestock. It is an important source of heat production in ruminants. Therefore, this can cause a stage of negative energy balance (NEB), which consequently result in body weight loss and reduced body conditioning.

In ruminant animals, an

increase in environmental temperature will alters the physiological mechanisms of the rumen which negatively affects the ruminant with increased risk of metabolic disorders and health problems. Researches had reported that under HS condition, ruminants produce less acetate whereas propionate and butyrate production increased as the rumen function is altered. Thus making the animal to consumed less roughages, changes rumen microbial population and pH from 5.82 to 6.03, decrease rumen motility and rumination. These inturn affects the animals health by lowering saliva production, variation in digestion patterns and decrease dry matter intake (DMI). Moreover, HS also results into hypofunction of the thyroid gland and affects the metabolism patterns of the animal.

IMPACT OF HEAT STRESS ON ACID-BASE BALANCE IN LIVESTOCK STOMACH

Animal under HS has increased respiration rate (RR) and sweating. These are ways through which body fluid is lost, resulting in uncontrolled dehydration and blood homeostasis. As RR increases, expiration of CO2 through the lungs also increases. This results to respiratory alkalosis, as blood carbonic acid concentration decreases, thus increasing the blood pH level. Therefore, animals will need more fluid to compensate for the lost ones. To increase the carbonic acid in the blood, bicarbonate must be excreted through urine to maintain the carbonic acid to bicarbonate ratio.

Chronic hyperthermia also causes severe or prolonged inappetence which further aggravates the increased supply of total carbonic acid in the rumen and decrease ruminal pH thereby, resulting into subclinical and acute rumen acidosis.

IMPACT OF HEAT STRESS ON ANIMAL IMMUNE SYSTEM

The immune system is the major body defense systems to protect against infection and make animals cope with environmental stressors. HS causes damage of the immune system in livestock and poultry, resulting in immune suppression, reduced disease resistance, and easy infection by various pathogens. This leads to increased morbidity and mortality of animals.

The immune system can be divided into non-specific and specific immunity. Specific immunity is composed of humoral and cellular immunity. Actually, many types of immune cells of the immune system play a role in both humoral and cellular immunity. The primary indicators of immunity or immune cells response include white blood cells (WBCs), red blood cells (RBCs), hemoglobin (Hb), packed cell volume (PCV), glucose and protein concentration in blood. All can be altered during thermal stress. WBC (leukocytes) count increase by 21-26% and RBC count decrease by 12-20% in thermally stressed cattle due to thyromolymphatic involution or destruction of erythrocytes.

Reseach had reported that there is high significant variation of Hb, PCV, plasma glucose, total protein and albumin when exposed to different temperature variation in malpura ewes. This higher PCV value was an adaptive mechanism to provide water necessary for evaporative cooling process.

However, in contrast to these findings, reduction of Hb and PCV levels were observed as a results of RBC lysis either by increased attack of free radicals on its membrane or inadequate nutrient availability for Hb synthesis as the animal consumes less feed or decreases voluntary intake upon HS.

In heat stressed cattles, it has being discovered that blood glucose significantly decreased in dairy cows in accordance to greater blood insulin activity. Release of plasma cortisol increases in stressed animals which causes down-regulation or suppression of L-selectin expression on the neutrophils surface.

Some clinical illlnesses had also been observed in animals under high air temperature. Lameness increases with an increase in air temperature, due to increase in standing time. Furthermore, lameness causes thin soles, white line disease, ulcers, and sole punctures and increases the likelihood for early culling from the herd.

Climate change may bring about substantial shifts in disease distribution and outbreaks. Change in rainfall and temperature regimes may affect both the distribution and the abundance of disease-causing vectors. The increase in THI has being discovered to result in increased incidence of mastitis in cows. the high incidence of mastitis in dairy cows could be due to high temperatures facilitating survival and multiplication of pathogens carrier fly population associated with hot-humid conditions. Excess heat load in extreme cases not only compromises animal welfare but also results into death of the animals.

EFFECT OF HS ON PRODUCTION AND REPRODUCTION PERFORMANCE OF DAIRY ANIMALS

MILK PRODUCTION AND COMPOSITION

HS adversely affects milk production and its composition in dairy animals, especially animals of high genetic merit.

HEAT stress impact on milk production depends on the duration and intensity of exposure to high temperatures and relative humidity. Dairy cattle that produce more milk are more sensitive to heat stress. This is because higher milk production levels increase the amount of metabolic heat that the cow produces. Also, heat stress do reduce the amount of feed consumed by animals, therefore reducing milk production. These has being supported by various researches estimating that effective environmental heat loads above 35°C activate the stress response systems in lactating dairy cows. In response, dairy cows reduce feed intake which is directly associated with NEB, which largely is responsible for the decline in milk synthesis.

HS during the dry period (i.e., last 2 months of gestation) reduced mammary cell proliferation and so, decreases milk yield in the following lactation. Moreover, HS during the dry period negatively affects the function of the immune cell in dairy cows facing calving and also extended to the following lactation .

As heat stress limits milk production, it also has negative impact on cow’s health, reproduction, and general well-being.

Temperature-humidity index (THI) is a common way to measure heat stress in dairy cows. THI is calculated using air temperature and relative humidity.

Dairy cows that are exposed to high temperatures and humidity may have inadequate body temperature regulation, which can lead to heat stress.

The earliest sign of heat stress in dairy cows is an increased breathing rate. When the rectal temperature (RT) >39.0°C and respiration rate (RR) >60/min in cows, this indicated that the animal is undergoing HS, thus affect milk yield and fertility.

HEAT stress also has severe effect on stages of lactation. Animals in their mid-lactation stage are mostly heat sensitive compared to early and late lactating counterparts. For example, the average milk production in Holstein-Friesian during early lactation period (first 60 days of lactation) was discovered to be higher in spring than in summer seasons. Similarly, early lactating dairy goats under HS produce greater milk yield losses (9%) compared to late lactating animals (3%). In addition, greater reductions in milk fat at early lactation (12%) has being discovered compared to their late lactation (1%).

Hot and humid environment not only affects milk yield but also affects milk quality. Researches had reported that milk fat, solids-not-fat (SNF) and milk protein percentage decreased by 39.7, 18.9 and 16.9%, respectively under heat stress condition.

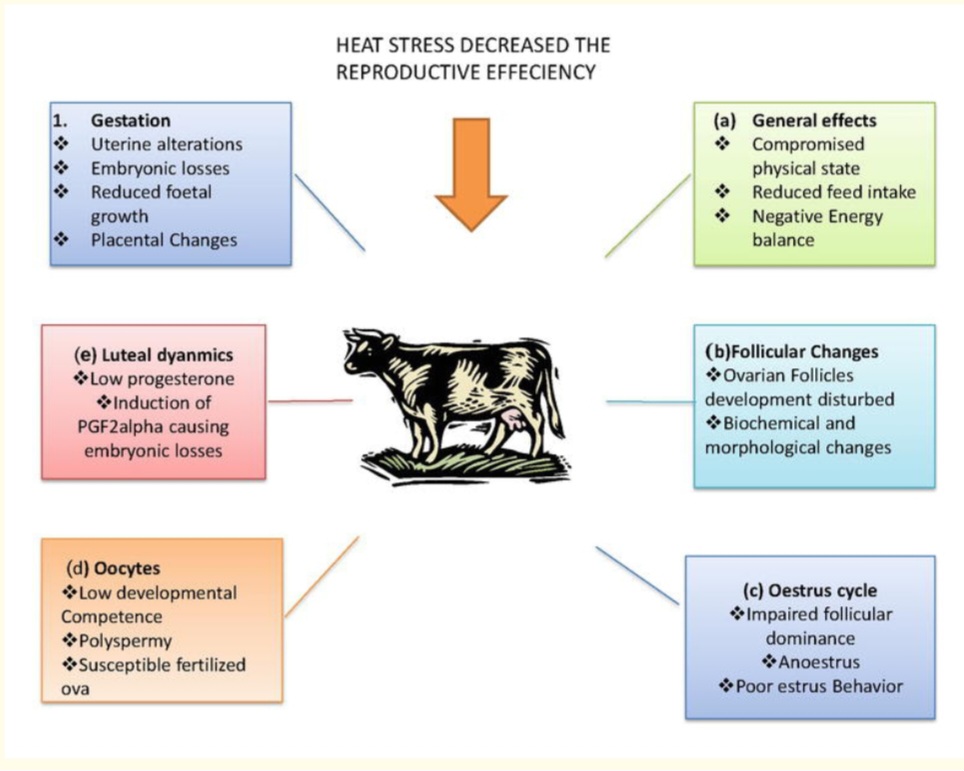

EFFECTS OF HEAT STRESS ON REPRODUCTIVE PERFORMANCE

The reproductive performance of livestock and poultry can seriously be affected by heat stress. Three mechanisms are involved for the decrease of reproductive efficiency in animals under Heat Stress. Firstly, the decrease in food intake, digestion, and absorption caused by HS leads to a decrease in energy intake or imbalance of nutrition, consequently affecting spermatogenesis, and ovarian and fetal development. Secondly, HS induces an imbalance of secretion of hormones which are involved in ovulation. It affects the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).

When the air temperature and humidity are high, cellular functions become affected by direct alteration and impairment of various tissues or organs of the reproductive system in both the sexes of the animal.

Heat stress significantly impacts animal reproductive performance by disrupting various aspects of the reproductive cycle, including oocyte quality, sperm motility, embryo development, and hormone regulation, leading to decreased fertility rates, reduced conception rates, and lower pregnancy success in both male and female animals. Essentially, high temperatures can negatively affect the production of viable offspring by impairing gamete development and early embryonic stages.

EFFECTS ON FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE PERFORMANCE

(Estrous period and follicular growth)

Heat stress is a significant factor that affect female animal reproductive performance. It causes a detrimental effects of elevating the animal’s body temperature on ovarian function and early embryo development. It disrupt the various aspects of the estrous cycle, including reduced estrus expression, impaired follicular development, decreased oocyte quality, lower conception rates, and increased embryonic mortality. This ultimately leads to lower fertility and reduced reproductive efficiency.

Also on estrus, HS reduces the duration and intensity of estrus. It increases incidence of anestrous and silent heat in farm animals. These reduced factors makes it harder to detect the optimal time for mating, leading to missed breeding opportunities.

As the heat stress increases, ACTH and cortisol secretion also increases, thus, blocking the estradiol-induced sexual behavior in the animal.

HEAT stress also impact the development of follicles in female animals. In a research, the study reveals that at temperature above 40°C, development of follicles do suffer damage and become non-viable. It has also being reported that when female goats are exposed to temperature of 36.8°C and 70% relative humidity for 48 h, follicular growth to ovulation becomes suppressed. This is also accompanied by decreased LH receptor level and follicular estradiol synthesis activity.

Granulosa cells in the ovary are responsible for producing estradiol, which function in follicular development, estrous cycles, and ultimately, increase fertility in females. Heat stress significantly reduces estradiol secretion, primarily by impairing the function of granulosa cells, therefore reducing estradiol secreation. This decreases follicular development, disrupted estrous cycles, reduce gonadotropin surge, ovulation, transport of gametes and ultimately, reduced fertility in females exposed to high temperatures.

A temperature rise of more than 2°C in unabated buffaloes may cause negative impacts due to low or desynchronized endocrine activities particularly pineal-hypothalamo-hypophyseal-gonadal axis altering respective hormone functions. In addition, research has also reported that low estradiol level on the day of estrus during summer period may be the likely factor for poor expression of heat in Indian buffaloes.

FERTILITY

Heat stress is one of the factors that significantly reduce livestock fertility by impairing various reproductive processes in both males and females animals, including decreased ovulation rate, reduced sperm quality, disrupted embryonic development, and altered hormone levels, ultimately leading to lower conception rates and decreased reproductive efficiency. It reduces oocyte development by affecting its growth and maturation. It increases circulating prolactin level in animal’s resulting to acyclicity and infertility. Moreover, 80% of estrus may be unnoticeable during summer in temperate regions which further reduces fertility.

In female animals,

heat stress result in reduced estrus detection, lessening the intensity and duration of estrus, making it harder to identify the optimal time for insemination. A period of high-temperature do results in increase secretion of endometrial PGF-2α, thereby threatening pregnancy maintenance leads to infertility. Also, it disrupt the normal development of follicles in the ovary, impacting oocyte quality. In cattle for example. Heat stress brings about increase in plasma follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) surge and inhibin concentrations decrease. This leads to variation in follicular dynamics and depression of follicular dominance that could be associated with low fertility in cattle during the summer and autumn. However, FSH secretion is elevated under HS condition probably due to reduced inhibition of negative feedback from smaller follicles which ultimately affect the reproductive efficiency of dairy animals

Several researches has also proven the negative effect of heat stress on rate of conception.

Oocytes of cows exposed to thermal stress do lose their competence for fertilization and development to the blastocyst stage.

Therefore, in the temperate region, it has being discovered that conception rates in dairy cow had dropped from about 40% to 60% during the cooler months to 10-20% or lower in summer, depending on the severity of thermal stress. A study had revealed that about 20-27% drop in conception rates or decrease in 90-day non-return rate to the first service in lactating dairy cows were recorded in summer. Moreover, during severe HS, only 10-20% of inseminations resulted in normal pregnancies during another study.

EMBRYONIC GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Heat stress negatively affect early embryonic development, increasing the risk of embryo loss and disrupt the normal secretion of reproductive hormones like estrogen and progesterone, leading to irregular cycles.

High temperatures during early embryonic development can increase the rate of embryo death, further reducing pregnancy rates. This occurs when HS interfers with protein synthesis, oxidative cell damage, reducing interferon-tau production for signaling pregnancy recognition and expression of stress-related genes associated with apoptosis. Low progesterone secretion limits endometrial function and embryo development. When lactating cows are exposed to HS on the 1st day after estrus, the embryos that developed to form the blastocyst stage becomes reduced on the day 8th after estrus. Further, exposure of post-implantation embryos (early organogenesis) and fetus to HS also leads to various teratologies. Most effects of HS in the embryo are most evident in early stages of its development. However, embryos subjected to high temperatures in vitro or in vivo until day 7 of development (blastocyst) showed lower pregnancy rates at day 30 and higher rates of embryonic loss on day 42 of gestation and lactation yield as well as postpartum ovarian activity.

EFFECTS ON MALE REPRODUCTIVE PERFORMANCE

Heat stress can significantly reduce sperm motility, morphology, and viability, impacting fertilization potential. It can lower male sexual desire and also affect mating behavior.

Bull testes must be 2-6°C cooler than core body temperature for fertile sperm to be produced. Therefore, increased testicular temperature results from thermal stress may cause changes in seminal and biochemical parameters leading to infertility problems in bulls. Several researches had proven that seasonal difference in heat effect can affect semen characteristics. Researches has reported that younger bulls are more sensitive to elevated air temperatures during the summer seasons. Other studies has reported that HS do affect the performance of spermatozoa. It highly reduces fertilization rate in comparison to non-HS or normal control spermatozoa. It significantly lowers conception as well as fertility rates per insemination of male and subsequently reduces male’s fitness.

EFFECT OF HS ON ANIMAL ENDOCRINE SYSTEM

The endocrine system is mainly composed of endocrine organs (such as pituitary, thyroid, thymus, and adrenal gland) and endocrine tissues (islets, luteal cells, etc.) that exist in other organs and tissues. Endocrine system regulates a variety of physiological activities through secretion of hormones. The regulation of hormones is mainly controlled by the feedback regulation and the central nervous system. The normal physiologic state of the body requires maintenance.

MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION OF HEAT STRESS IN LIVESTOCK AND ON THE FARM

Extreme heat causes significant stress for all animals. It is the responsibility of owners or people in charge of animals to be well prepared for heat events to ensure the welfare of their animals is maintained.

Some of the significant impacts of heat stress is on production and animal welfare, by making some minor management changes and taking a little extra care of the animals during periods of extreme hot weather, the effects of heat stress can be substantially reduced. Some of the management practices include: forward planning of farm infrastructure to provide shaded areas with good ventilation to maximise heat loss, checked animals regularly throughout the day for signs of heat stress, along with water points to ensure animals have access to ample cool water. Some of the management practices include;

1. PROVIDE PLENTY WATER TO DRINK;

The provision of plentiful clean, cool water and shade is essential in managing heat stress. Plenty of cool clean water should be offered but they should be encouraged to drink small amounts often.

Water troughs or containers should be large enough and designed in such a way that all animals have easy access. The number of watering points and water flow should be increased if a large number of animals are kept together.

Troughs or containers should be firmly fixed so they cannot overturn. They should be kept clean and should be designed and maintained to prevent injuries. Large concrete troughs help keep drinking water cool.

The location of water should be familiar to animals in the days before extreme heat occurs. Animals should not have to walk too far for water. If putting livestock into a new paddock, especially where pasture is high, ensure they are familiarised with watering points as the height of pasture may prevent them from seeing the water sites (especially young or small stock).

2. TYPES OF SHELTER TO PROTECT FROM HEAT

Animals need to be provided with shelter during extended periods of extreme temperatures. Shelter is especially important for very young or old animals and animals that are in poor condition or sick.

The best type of shelter during extreme heat protects the animals from the sun and allows for the cooling effect of wind.

Also, Holding and processing areas for livestock should have shaded areas available. Use of water sprinklers or misters can be useful to cool some species such as pigs and cattle.

3. RISK OF SMOTHERING

If insufficient shelter is provided for large groups of livestock there is the risk of animals crowding together under shelter resulting in smothering. It is important that shelter is available to all animals at the same time. It is preferable that shelter includes sufficient room for all animals to be able to lie down, as this assists with cooling.

It may be necessary to divide the number of animals into smaller groups. Group mentality may mean that even when animals have access to several smaller areas of shelter they will tend to camp together crowding under one source and around water.

4. OUTDOOR POULTRY HOUSES

Outdoor poultry houses (for example free range set ups or backyards) should be positioned in an area that is shaded from the sun and has good airflow. The east and west walls can be insulated. Wide overhangs at the eaves and solid end walls can also be used. In addition, an angled roof will reflect more heat at the hottest time of the day if the face of the slope is not directly facing the sun. The construction and positioning of nest boxes should be such that they avoid becoming heat traps.

5. REDUCE ANIMAL HANDLING: Avoid unnecessary handling, yarding, or transport during hot weather. Rather, use low-stress handling techniques

It is recommended not to handle animals in extreme heat unless absolutely necessary. If necessary, the handling should be done as early or late in the day as possible when temperatures are lower. For example, newly hatched chicks and other newly born animals should be transported early in the morning or late evening to reduce stress.

Also, research has shown that movement or handling of cattle during hot weather can increase their body temperature by 0.5 to 3.5° C. Increased body temperature or heat stress will cause production losses in livestock and impact on their ability to maintain normal function.

Moving animals during cooler hours can decrease the impact of high temperatures on production performance. For example, a delay in milking by an hour or more in the evenings can result in an increase in production of up to 1.5 litres/day/cow.

6. TRANSPORTING ANIMALS DURING THE HEAT

Transport of animals should be planned, especially in extreme climatic so as to avoid compromising the animals’ welfare.

If transport is absolutely necessary, the journey should be planned so as to minimise the effects of hot weather on the animals.

Transportation routes should be along places with shades and water availability (such as rest stops). Animals should only be transported during the cooler hours of the day.

If it is necessary to stop, vehicle should be packed under the shade and at right angles to the wind direction to improve wind flow between animals during hot weather. Duration of stops should be kept to a minimum to avoid the build-up of heat while the vehicle is stationary.

Stocking densities should be reduced to 85% of capacity to ensure good air flow between animals, and drivers should have contingency plans in place for the occurrence of adverse weather events

7. PROVIDE SHADE: Provide shade to keep animals cool by constructing shaded areas outdoors and using shade cloths in barns.

But when animals are faced with heat stress, move them to the shade immediately, preferably somewhere with a breeze. If animals are too stressed to move, pick them up and move them or provide shade where they are.

8. INCREASE VENTILATION: Utilize fans and natural ventilation systems to improve air circulation in the pen house. But when heat stressed, increase air movement around them using fans, ventilation, or wind movement.

9. COOLING SYSTEMS: Implement sprinklers or misting systems to provide evaporative cooling. When heat stressed, spray them with cool water, especially on the legs and feet, or stand them in water. Use sprinklers or hoses for cattle, pigs and horses.

In addition, when animals are heat stressed, Lay wet towels over them. Dogs and cats can be placed in buckets/troughs of cool water. Poultry should not be wet down unless there is a breeze to aid the cooling process.

10. ADJUST FEEDING TIMES: Feed animals during cooler parts of the day.

11. DIETARY ADJUSTMENTS: Modify feed rations to include higher levels of water and electrolytes.

12. GENETIC SELECTION: Climate-smart breeds can be bred which are thermotolerance. Cattle and other ruminants with shorter hair, hair of greater diameter and lighter coat colour are more adapted to hot environments than those with longer hair coats and darker colours. Breeders should breed animals with traits that enhance heat tolerance.

13. PLAN ROAMING PERIODS: Work animals in the early hours of the morning

14. FEEDING:

Reduced food intake is an adaptive protection mechanism for managing heat stressed animals. In pigs for example, when the ambient temperature is higher than the optimum temperature, the feed intake decreases significantly. The appetite control center of animals is located in the hypothalamus. High environmental temperature activates the capsaicin receptor 1 (TRPV1) like receptor in the Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus, and the expression result in loss of appetite in the animal.

Feed digestion causes heat production which contribute to the animals heat load. Provide animals with high quality feed to maintain nutrient intake without excessive heat production, and feed out in early morning or evening when temperatures are lower.Also, consider feeding animals supplements to help support their immune system

15. REGULAR SUPPLY OF WATER: Provide clean water for drinking on regular basis. Also, cold water can be provided for drinking.

16. VITAMIN AND MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS: HS causes oxidative damage which could be minimized through supplementation of vitamins C, E and A and also mineral such as zinc. Vitamin E acts as an inhibitor – “chain blocker”- of lipid peroxidation and ascorbic acid prevents lipid peroxidation due to peroxyl radicals. It also recycles vitamin E, vitamin C and zinc are known to scavenge ROS during oxidative stress. Further, vitamin C assist in the absorption of folic acid by reducing it to tetrahydrofolate, the latter again acts as an antioxidant. Use of vitamin C along with electrolyte supplementation was found to relieve the animals of oxidative stress and boosts cell-mediated immunity in buffaloes .

17. MODIFY ANIMAL HOUSING: Use heat extractors, fans, water sprinklers, and cool drinking water.

18. MATCH BREEDS TO PRODUCTION SYSTEMS: Match adapted ruminant breeds to appropriate production systems.

19. STOCKING DENSITY: Decrease stocking rates to allow animals room to lie down.

20. If the animal shows no sign of improvement contact your local vet for assistance.

In conclusion, high temperature has detrimental effect on animal health. Therefore, it is important for all animal owners to care for their animals and emback on proper heat stress management practices to keep their animals live, in good health and make them happy.

Your blog is a guide of knowledge, always sparking curiosity and motivating deeper thought. It would be intriguing to see you examine how these ideas intersect with contemporary shifts, such as artificial intelligence or sustainable living. Your knack for breaking down complex subjects is remarkable. Thanks for consistently delivering such engaging content—I’m excited for what’s next!

Information: https://talkchatgpt.com/

чат gpt для текста

Hi Anthonyze,

Thank you for your worm compliment and encouragement. Supremelights is highly delighted, hearing from you and your motivating words. We appreciate you. If you have any aspect of agriculture you want us to address or any clarification from the posts, please be free to contact us.

Bye